by Emily Rinaman, Technical Services Manager

Art is a broad field. If you go to any art museum, you’ll find several wings representing so many styles of art – paintings from the classic artists like Picasso, Rembrandt or Monet to contemporary and modern sculptures and just about everything in between.

Like most art, billboards and comic strips are two niche forms of art that supply a message of some kind. Billboards usually involve a persuasive theme trying to sell an item or service, although sometimes they are trying to sway your opinion.

Comics are similar in nature; they often lightheartedly poke fun at an issue to which many people can relate (part of the reason why they are often referred to as “the funnies”). For example, pictured is a comic designed by a fellow college student that was placed in the January 1973 edition of Tiffin University’s student newspaper, the Tystanac. It needs no explanation, at least for folks who can recall their college orientations spent in the university bookstore scrambling to get all the required textbooks before the first day of class. It was included in a set of comics under the collective title, “What! College?”

Historically, comics have been infamous for sharing political opinions, which continues today. Tiffin’s League of Women Voters group state in their September 1971 board meeting minutes that they had gathered humorous cartoons from newspapers and magazines for a poster on state water resources and air pollution to illustrate their presentations with relatable facts and figures.

One of the ways that small business owners would share their products and services was to get an advertisement painted on the side of a building. These can often still be seen on old brick buildings and are often discovered when renovations are being done (due to the lead in the oil-based paint that helped it adhere to the building better). To historians, they are known as “ghost signs” because they remain on the buildings well after the business to which they were once attached.

Ghost signs were heavily used from the 1880s-1950s until neon signs and the modern billboard started taking over. Highly visible brick walls or walls on buildings along railroads were typical spots. When New Riegel’s depot was used, advertising posters were often framed on the walls and in 1996, some of these had been donated to the Seneca County Museum.

Besides products, billboards also sold (and still do) ideas that the artists wanted to not just share, but persuade others into believing alongside him, her, or them (if it was an organization). One such way was murals, whose popularity nestled into the tail-end of the ghost sign era but before the neon lights debuted.

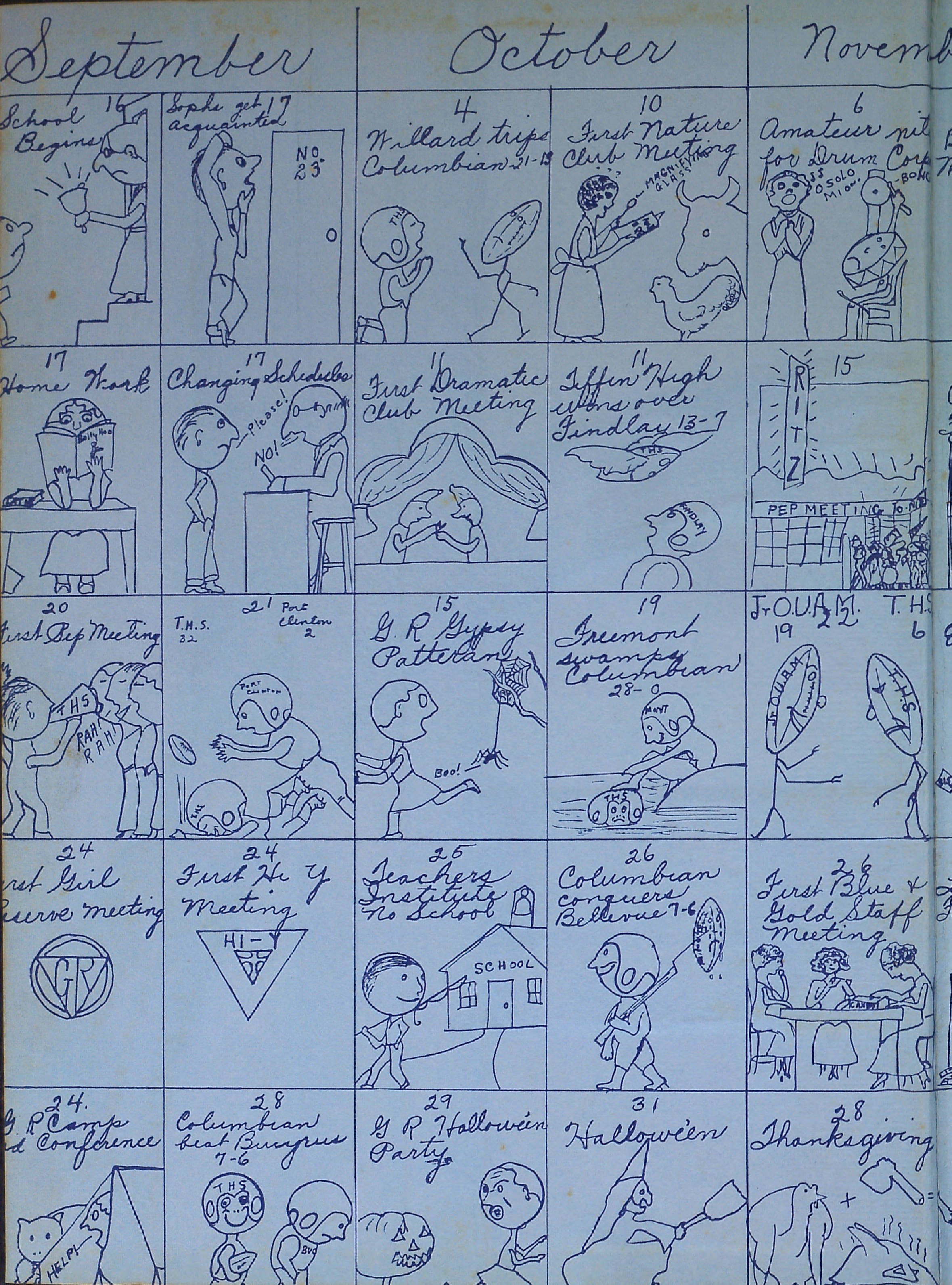

A “cartoon calendar” found the Columbian Blue and Gold 1936 yearbook. (Artist unknown)

During the New Deal, the U.S. Works Progress Administration commissioned for murals that would “lift the spirits of a nation in the grips of the Great Depression.” Thousands of murals were painting showing farmers, factory workers and American icons like Abraham Lincoln. During World War II, Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” paintings “were such a patriotic inspiration and phenomenal success” that they were eventually used in a campaign to sell war bonds and stamps.

Myron Barnes recalls in “Seneca Sentinel Bicentennial Sketches” that as a child growing up in Tiffin, there were posters hanging in multiple windows of the former courthouse portrayed various aspects of the Great War, including the Victory loans from that war. In addition, a map of the Western Front was updated daily by the Advertiser Tribune with news of battles. He and his friends, who were “inspired” by the posters and map, bought war savings stamps. If enough were saved, they were turned in for hefty bonds (Byron eventually bought his first car with these stamps).

Creating posters for political propaganda was not something new, however. As far back as the Civil War, posters of political ideas were being created. General William H. Gibson (“Ohio’s Silver-Tongued Orator”) used this method to help recruit local men for the Union. He put a poster on the north wall of the Army post that said, “To ARMS! To ARMS! Rally to Our Flag! Rush to the Field! Are we cowards that we must yield to traitors? Come one, come all! Let us march, as our forefathers marched, to defend the only democratic Republic on earth!”

While this particular poster was probably made in haste since it was extremely time-sensitive, comics were approached with more reverence. In the first part of the 20th century when newspapers and magazines were beginning to become a mainstay in American society, the job of an illustrator paid very well. In fact, in a time when Hollywood actors and actresses didn’t exist yet, illustrators were the main celebrities. They were always in high demand because they were talented artists who could swiftly spread ideas through their creations to the masses.

When television did come around, comics adapted into the “moving pictures.” Another edition of the T.U. Tystanac gives praise to the Pink Panther, as a segment quite often appeared before the main show at the movie theater and was also a main classic Saturday morning cartoon. Likewise, a student at Calvert in the late 1980s, Tom Batuik, drew a cartoon to illustrate an appreciation letter written by Calvert and Seneca East students thanking the Advertiser-Tribune fore reinstalling the Funky Winterbean comic (shown here).

Children and young teenagers are still often encouraged to put their illustrating and persuasive skills to the test in billboard contests. Earth Day in late April always brings with it, enlargements on billboards of cleverly displayed messages from local students on why it’s important to recycle.

Works cited:

Bigger, David Dwight. Ohio’s Silver-Tongued Orator. 1901. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/39307

Barnes, Myron. Seneca Sentinel Bicentennial Sketches. 1976. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/33781

Buckholtz, Sarah. “Walldogs—the Artists Behind Ghost Signs.” Antique Archaeology. May 11, 2017. https://www.antiquearchaeology.com/blog/tag/brick-ads/

Kruchak, Matthew. “Your City’s ‘Ghost Signs’ Have Stories to Tell.” Bloomberg. August 17, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-17/-light-capsules-reveal-the-history-of-cities-faded-ads

League of Women Voters of Tiffin Interim Report 1971-09-01. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/67717

MacDonald, Christine. “Street Art Used to Be the Voice of the People. Now it’s the Voice of Advertisers.” In These Times. March 11, 2019. https://inthesetimes.com/article/street-art-murals-corporations-advertising-los-angeles-muralism-graffiti

Normal Rockwell Museum. Illustration History. “Comic Strips.” https://www.illustrationhistory.org/genres/comics-comic-strips

Official Souvenir Glass Festival 1965. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/36379

Seneca County Museum Newsletter Winter 1996. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/43136

Library of Congress. Classroom Materials. “Political Cartoons and Public Debates.” https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/political-cartoons-and-public-debates/#:~:text=Political%20cartoons%20began%20as%20a,as%20being%20published%20in%20newspapers

Yearbook Calvertana 1989. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/19241

Tiffin University. Tystenac 1971-10. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/43655