by Emily Rinaman, Technical Services Manager

As the leaves begin to change color and chilly air begins to slowly creep its way in, especially in the crisp evenings of fall, many people begin to get into a certain spirit – a spirit for Halloween. Halloween has its share of decorations honoring the Grim Reaper, spooky haunted houses in the form of dilapidated Victorian homes, and wooden coffins. But if you dig deeper (yes, pun intended), you’ll find a lot of truth to these widely popular symbols for the October holiday.

Funeral and mourning practices have stayed relatively unchanged for a long time, at least on the surface. Modern-day funeral “homes” are usually old Victorian homes that have been refurbished and remodeled to great extents. During Victorian times when these homes functioned as houses, they were still the actual sites of funerals so the locations really haven’t changed.

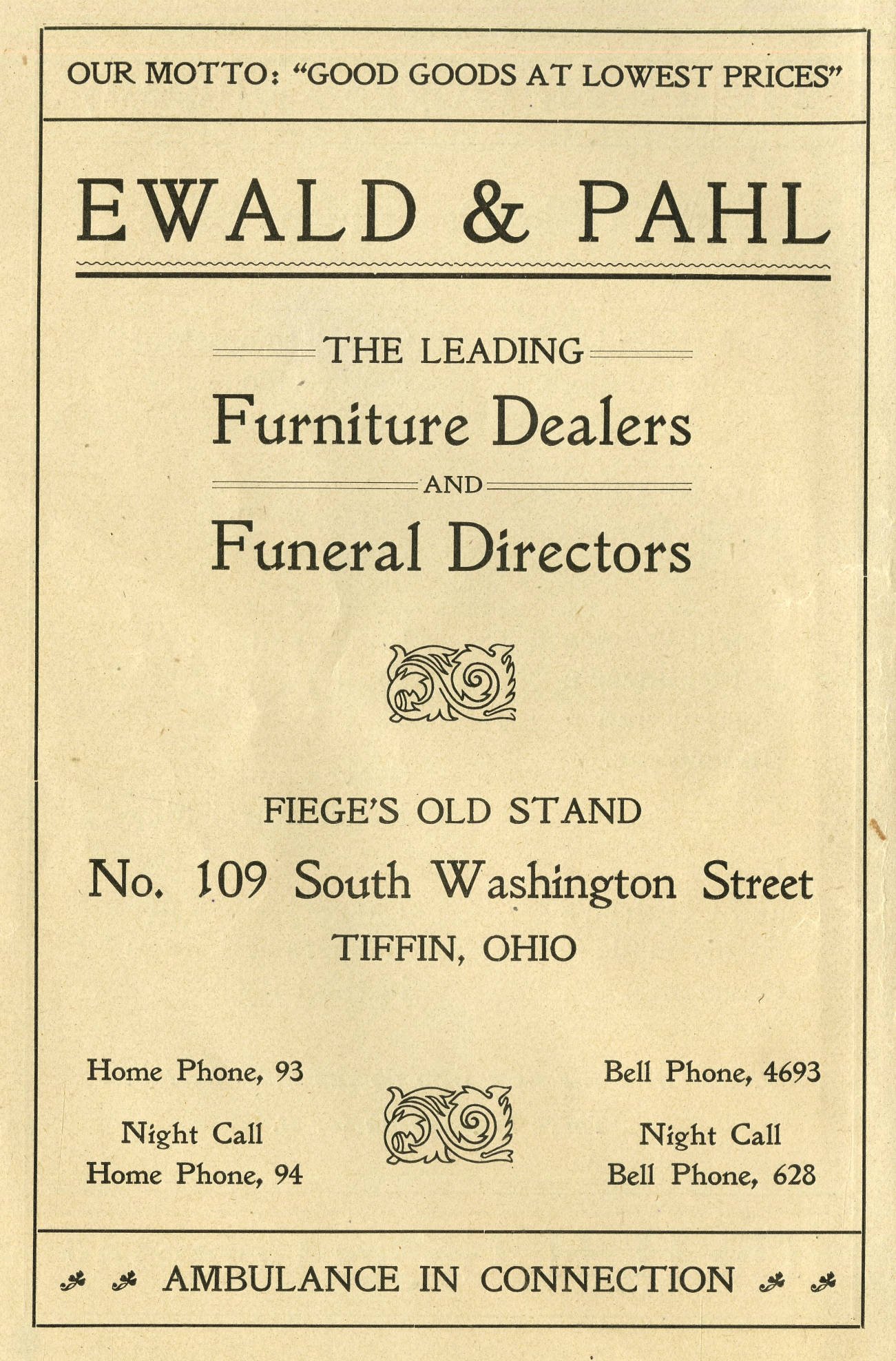

An ad for Ewald & Pahl, funeral directors in Tiffin around the turn of the century. This was taken from the Historical Sketches of Churches and Schools of Tiffin, Ohio 1903, which has been digitized onto the Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/63773

A long time ago, homes had parlors. The parlors were formal rooms in the front of the house where people entertained their visitors. But they were also the sight of more macabre events, which is why funeral homes were first called funeral parlors before that term died (yes, another pun intended).

Larger cities were the first to switch over to official funeral homes, but in smaller towns like Tiffin and its surrounding communities, the practice of using parlors continued well into the 1940s.

Once funeral homes began, they were often succeeded by the next generations of the same family. For example, Green Springs had a funeral parlor owned by the Young family from the 1940s-1960s and Harrold-Floriana Funeral Home in Fostoria is a fifth-generation funeral home.

It usually took three or four generations until forces combined. It was during the 1970s and 1980s that hyphenated names for funeral homes began appearing as two separate homes would often be consolidated. Other local funeral homes saw this same pattern. Adam Turner turned the Loomis home into a funeral home in 1946. His apprentice, Phillip Engle, took over when Turner passed away in 1965, renaming is the Turner-Engle Funeral Home. Turner-Engle is now known as Engle-Shook Funeral Home with locations in Tiffin, Bloomville and Bettsville.

According to its website, The Hoffmann-Gottfried-Mack Funeral Home began as simple the Hoffmanm Memorial Funeral Home in 1914. In 1937 it bought the Sewalt Mansion (its current location). It combined with the Gottfried Memorial Funeral Home in 1986 and to its current name in 2004.

While funeral homes serve these functions now, in the 1800s and early 1900s, family members, their friends and sometimes their wait staff/servants, were the first people who handled a deceased body of a loved one. There was no call to these funeral homes for a body to be taken away for preparations. Bodies were laid out in the parlors and people came to the house for both the visitation and funeral service. In between, the family kept constant vigil over the body.

An ad for A. Niebel, undertaker, in Tiffin. This was taken from the Tiffin Fremont and Fostoria City Directory 1874-1875, which has been digitized onto the Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/27713

The only call made was to the undertaker for a coffin. In the early years of our country, coffins were typically made by cabinet makers. Tiffin had four cabinet makers and by the 1860s, there was only one official undertaker. In the What How and Who of It: An Ohio Community, it states Dick Rogers operated the “coffin-making shop.”

While walnut was the most common material used, upscale coffins could be double the price as the plainer ones. Bascom’s cabinet/coffin maker, William Dewald had a wife, “Bessie,” who designed the padded liners for his coffins, often adding embroidery (probably for an extra charge). Oak and pine woods were used until the 1870s, eventually being replaced by rarer woods and metals, like silver, bronze, copper and stainless steel.

Eventually undertakers started offering hearses along with the coffin as a package deal, which often used handmade artwork to create similar tiered pricing. Hearses would park next to the “coffin window” of the parlor (these are extra large windows that can still often be seen in older homes today).

Policeman Patrick Sweeney was killed on duty in 1909. Before embalming became a widespread practice with state laws, funeral flowers were placed near the decaying body to mask the odor.

Last, but certainly not least, are the flowers. While sending flowers to a funeral visitation is a form of condolence, flowers were originally included in funeral practices simply to mask the smell of the decaying corpse (candles were often also used). “Depending on many factors, such as the environment and the condition of the body, flowers were used in varying quantities as a way of tolerating the smell for those who came to pay their final respects.” So, in essence the flowers were to console the visitors until embalming became the norm and laws were created.

Often, the floral display included a wreath. In the Bascom Area Sesquicentennial, there are photos of funeral flowers displayed around a clock. Policeman Patrick Sweeney, who was killed in action, has flowers surrounding a photographer of him at his funeral in 1909 (see photo). In Tiffin, Edmund Ulrich and later his son, Lewis Ulrich, were an early supplier of funeral flowers in the early 1900s for area families. Their greenhouse was located on Sycamore Street. Wagner’s Florals, however, was the first having been founded in 1847. Rodger’s Flowers followed 100 years later (1947).

Works cited:

Barnes, Myron. Seneca Sentinel Bicentennial Sketches. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/33669

Bascom Garden Club. Bascom Then and Now. 1976. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/29193

Baughman, A.J. Seneca County History Volume 2. 1911. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/17468

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. “Funeral Homes and Funeral Practices.” Case Western Reserve University. https://case.edu/ech/articles/f/funeral-homes-and-funeral-practices

Green Springs Centennial Committee. Green Springs Centennial. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/29439

Howe, Barbara. Building of the Week. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/28064

Petal Talk. “History of Funeral Flowers.” https://www.1800flowers.com/blog/flower-facts/history-of-funeral-flowers/

Scent & Violet Flowers & Gifts. “The Fascinating History of Funeral Wreaths.” Oct. 9, 2018. https://www.scentandviolet.com/info/blog/fascinating-history-funeral-wreaths/#.ZAdy7HbMKUl

Schmitt, Elizabeth Schlageter. “The History of Home Funerals: From Family Tradition and Back Again.” National Funeral Home Alliance. https://www.homefuneralalliance.org/home-funeral-history.html

Smith, Howard. The What, How and Who of It: an Ohio Community. 1997. Seneca County Digital Library. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p15005coll27/id/15879

Weber, Austin. “The History of Caskets.” Assembly Magazine. Oct. 2, 2009. https://www.assemblymag.com/articles/87043-the-history-of-caskets

“Where Did Funeral Parlors Originate?” Glicker Funeral Home & Cremation Service. https://www.glicklerfuneralhome.com/blog/where-did-funeral-parlors-originate/